All human beings are descendants of tribal people who were spiritually alive, intimately in love with the natural world, children of Mother Earth. When we were tribal people, we knew who we were, we knew where we were, and we knew our purpose. This sacred perception of reality remains alive and well in our genetic memory. We carry it inside of us, usually in a dusty box in the mind’s attic, but it is accessible. – John Trudell

I love Australia and I love Melbourne. I find it to be as close to heaven on earth as any place on earth can be.

I came to Melbourne in 2002 from Mauritius as a 19-year-old to study at RMIT University. I instantly fell in love with the city. In 2007, I met and married my beautiful wife, a Mauritian girl I met at university and 15 years later, I have 3 beautiful girls and my wife and I run businesses engaged in the promotion of Mauritian culture in Australia.

I feel so grateful to be in this country. I feel so grateful to have been given the opportunity to build a life here. When I arrived and I understood that this country was the country of the fair go, that fairness reigns supreme on this land, being strong on fairness myself, I connected in a deep and meaningful way with Australia and its people. I could see fairness in so many walks of life from simple things such as how people queue up to it’s sports and the way for example that the AFL is structured in a way that gives every team a fair go at success. That same fairness can also be observed in the way Australians conducts business, giving people who have a good go, a genuine opportunity to succeed.

I also love Mauritius and wish to go and live there permanently one day, but the truth is that I come from a country where ‘who you know’ is more important than ‘what you know’. When we wanted to open a business in Mauritius, it took me weeks to get through the layers of red tape and become compliant. In Mauritius, if you know the right people or carry the right surname or if you look a certain way, a process that could take weeks will be wrapped up in a matter of days, even hours. In Australia, I felt so grateful that I was never asked where I am from or what my name is before we were allowed to set out building our business. We received support from all quarters, including awards and grants to help us improve our impact. The spirit of the fair go, embedded in the national psyche of Australia and its people, was something that we truly felt all this time, at least at our level of society.

In 2005, I was part of a delegation representing RMIT University at a conference held at Sydney University. We were staying at a Unilodge and on my first night there I had my first ever encounter with an aboriginal Australian. For the first 3 years of being in Melbourne, I had not once met with an Aboriginal person.

I was on my way back to my room when I saw him. He was just outside the room his room and nodded as he saw me. I was slightly taken aback. Before coming to Australia as well as when after arriving, I had heard many negative stories about Aboriginal Australians. I had heard that they are violent people, alcoholics, repeat offenders who I would do well avoiding. This guy looked super friendly however. I nodded back and he started chatting, asking me where I was from. Shortly afterwards, he invited me inside. I accepted and stepped in and saw a Caucasian looking guy as well. They were friendly and we started chatting away. The Causasian looking guy was a bit more reserved but still very friendly. I wanted to know more about Aboriginal people. I was directing my question to the Aboriginal man and he was totally fascinating. He was telling me about the Aboriginal people and what their lived experience of modern Australia is. After some time, I turned to the Caucasian looking guy and asked him what he made of all of this? Immediately I sensed tension. I was unsure what had caused it. I waited and the Aboriginal man told me that his mate was also an Aboriginal Australian but was part of the stolen generation, and he went on to tell me all about a program to ‘whitewash’ of Australia.

I was completely floored. I had absolutely no idea of what he had told me including how alcohol was introduced into their communities as a way of mass control and how completely messed up some Aboriginal communities were. After some time I left these two guys but that interaction is one I will take to my grave.

I came back to Melbourne and researched. Coming from a country that has experienced slavery and indentured labour, I empathised with the depth of cruelty that the Aboriginal people had lived through over the course of British settlement and became privately a supporter of stronger reconciliation efforts. In 2008 when Kevin Rudd gave the National Apology speech, I felt proud to be someone wanting citizenship of this country as I could see how despite quarters of resistance, that this country had so much goodness in it.

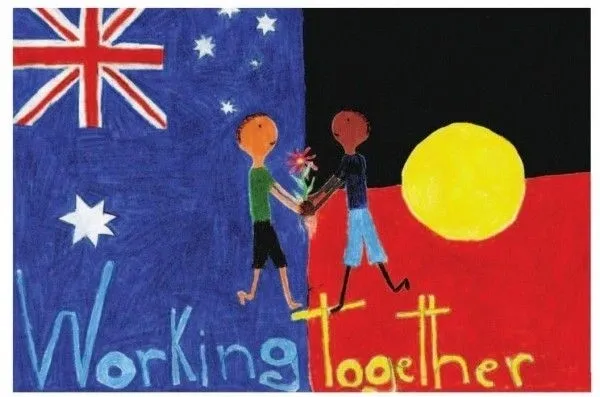

During one of the Melbourne lockdowns, a friend recommended I watch ‘The Australian Dream’, a documentary by Stan Grant about Adam Goodes. At the end of it, when Aussies who had ‘cancelled’ Adam, forcing him to take a premature break from the game because of his stand against racism, came together to ask him to come back, a few tears rolled down my cheeks.. This documentary cemented my strong belief that Australia needs reconciliation for “The greatness of a nation can be judged by how it treats its weakest member”. As a newly arrived migrant, I find myself torn on every Australia Day between celebrating the country and culture I fell in love with and the cry of its indigenous people who continue to suffer the harrowing pains of British colonisation.

Aboriginal culture is the longest living culture on this planet. It is a culture that deeply respects the land, the mother. It’s a culture that understands nature in ways modern humans don’t and may never again learn to. Back in 2004 when the Boxing Day tsunami hit, a tribal group of people called the Sentinelese who live on the Andaman and Nicobar group of islands survived the tsunami that had killed more than 225,000 modern humans around them. Scientists theorise that they could smell the wind, read the flight of birds and gauge the depth of the sea with the sound of their oars, possessing a very highly developed sixth sense which modern humans have lost, and it was that strong sixth sense that helped them move uphill as the tsunami waves crashed against their island. This is also the kind of knowledge that Aboriginal Australians possess, but that has been deemed worthless in this day and age. In 2011, when the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami hit Japan, more than 15,000 people died, despite the most advanced tsunami warning systems in place.

Sometimes I wonder whether this country is the lucky country because of the relationship between Aboriginal Australians and this land over a period of more than 60,000 years? Do we owe some of the natural richness of the land to that deep sense of respect and responsibility that Aboriginal Australians have for this land?

Today is another Australia Day when I feel torn. I celebrate this beautiful culture and people, one that made me leave my own motherland to come to, but I also mourn with the first people of the land who until now have been made to feel as outsiders in their own home, on their own land.

Australia is the land of the fortunate, the land of opportunity and equality, but it will never truly become the greatest it can be as long as Aboriginal Australians will continue to be made to feel lesser, inadequate and unwelcome. As for all the issues we see in Aboriginal communities, be it homelessness, domestic violence, alcohol abuse or repeat offending, they are all symptoms of the damage inflected on these communities over a period of more than 200 years. Dispossession and engineered low self-worth does this to people. We could continue focusing on these symptoms and further alienate, or focus on the root causes and seek to bridge and unite.

Aboriginal culture is not one that we should seek to accommodate. It’s a culture we should embrace and celebrate, as it is a national treasure. It’s a culture as unique to Australia as its Uluru. It’s a culture we should be teaching in all our primary and secondary schools, a culture that new migrants should be encouraged to learn more about and Australian children should grow up with. It’s a culture that we should be taking trips from our different cities to explore and deepen our understanding of. It’s a culture whose art we should all possess in our homes, and whose music we should use for meditation and mindfulness. It’s a culture that could be a leading voice on how we reconcile with mother Earth during this tumultuous age of disruption and upheaval. It’s a culture without which we are all poorer and with which, we will all be a lot richer.

This Australia Day I celebrate modern Australia as the land of the young and the free, the country of the fair go and I cry with Aboriginal Australia who get treated worse than second class citizens on their own land. This Australia Day, I pray for reconciliation.